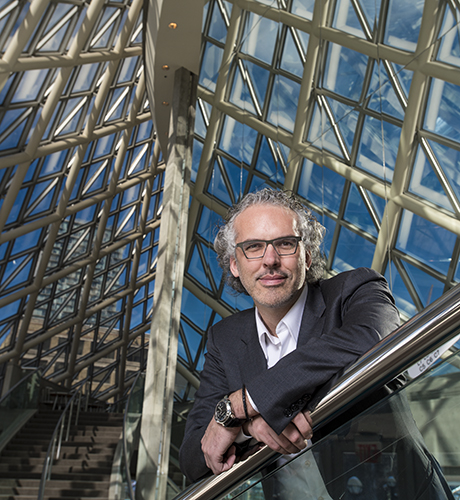

Photography by Mathew McCarthy

Most chief executive officers spend so much time wearing a suit and tie, that the outfit has become a de facto uniform. It’s so ubiquitous that the term “suit” has become a synonym for the higher ups in an organization, a term that often carries some less-than positive connotations.

Jeff Melanson, president and CEO of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, tries to avoid wearing a suit whenever he can. He only wears a tie when he absolutely has to. “They made me wear a suit because your photographer’s here,” he jokes as he settles into an interview in the lobby of Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall, the building’s iconic glass dome ascending overhead. “You did this to me.”

As Melanson (MBA ’99) describes his job and what keeps him motivated, he sounds, at times, like your standard “suit”, talking about spending his days in meetings and shifting economic models. But he takes on a different tone in describing his favourite part of his day: “At least once a day, I get to have one beautiful conversation with someone who’s got a great idea about changing the world or creativity and its application in society.”

Melanson is a trained opera singer — the main reason he doesn’t like wearing ties: “as a singer, it’s too constricting” — who also has his MBA. Memorable moments from his career include helping the National Ballet School of Canada to a massive increase in revenues, but also starting ballet lessons as a six-foot-six 33 year old — “I didn’t hurt anyone, or myself, so I’d say it was successful,” he quips on his time learning dance.

It is this unique combination of arts and business, a balance he honed during his time in Laurier’s MBA program, that led him to where he is today. “I could not be doing what I’m doing without both skill sets, there’s no doubt about that,” he says. “Sometimes if you’re an arts leader without business acumen, it’s harder to raise the kind of money you need to produce the kind of ideas you’d like to see come to fruition.

“But the artistic side inspires bigger thinking and imagination and creates a connection between your inner and outer worlds.”

Big ideas are something Melanson has brought to every stop of his professional career. His habit of challenging the status quo has led to a reputation as someone who can inject new life into some of Canada’s most entrenched arts institutions.

Big ideas are something Melanson has brought to every stop of his professional career. His habit of challenging the status quo has led to a reputation as someone who can inject new life into some of Canada’s most entrenched arts institutions.

At the age of 28, Melanson was appointed dean of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto after starting his arts administration career with Opera Ontario in 1999.. One of the first things he noticed was that the renowned Canadian music school was missing a wide range of the population.

“People would ask me, ‘what is it like to run one of the largest community music schools in the world in the world’s most ethnically diverse city,’ and the truth of it was, if you were to walk into that school you’d have no clue you were in Toronto,” says Melanson.

“We did a demographic study and discovered we were training a very, very affluent and not very ethnically diverse part of Toronto.”

During Melanson’s time at the helm of the Royal Conservatory, the school significantly broadened its horizons, adding academic programs in world music, jazz, rock and pop and even a DJ technique class. He also helped launch an urban arts program that brought music into underserved and less affluent communities in Toronto.

Melanson says working with Royal Conservatory president Peter Simon was what taught him the ins and outs of fundraising for an arts organization. His time with the Royal Conservatory also provided a handy lesson in dealing with push back from people entrenched in the status quo.

“You can imagine how some people reacted to adding a DJ program to the Royal Conservatory of Music; we got a lot of fun mail on that one,” Melanson says with a chuckle. “Change isn’t easy for everyone, but if you’re being driven by the right values and principles, it doesn’t really matter what someone says about you.”

After five years with the Royal Conservatory, Melanson was named executive director and co-CEO of Canada’s National Ballet School (NBS). At his first board meeting with the NBS, the main item on the agenda was bankruptcy. The school had lost $2 million the year before Melanson arrived and was on track to lose another $3 million the coming year.

True to form, Melanson led an unorthodox solution to the school’s money problems.

“The ‘normal’ way to react would be to cut your expenses by $2 or $3 million, but I’m an abnormal guy, so I didn’t really respond to that. What we did was we basically just put a full-court press on every revenue we could find,” says Melanson, who was also an adult student at the NBS during his time there.

Through an aggressive push for government funding and an ambitious fundraising campaign, the NBS saw its total revenues increase from $10 million in 2006 to $22 million in 2011, a dramatic improvement in the midst of an economic downturn.

Further proof of Melanson’s willingness to go against the grain: he was the arts adviser to former Toronto mayor Rob Ford. As Ford entered office in 2010 with promises of “stopping the gravy train,” Melanson agreed to be a liaison between the mayor’s office and Toronto’s arts community on one condition – that Ford not cut the city’s arts budget.

In 2012, Melanson would leave Toronto for a new position as president of the globally renowned Banff Centre. Nestled in the Canadian Rockies, the Banff Centre is one of the world’s leading arts institutions and Melanson calls being its president a “dream job.” He didn’t waste any time getting started, announcing plans to shift the centre’s vision towards becoming an arts incubator of sorts, developing content of all types and supporting artists; and also to expand the institution’s facilities and funding models.

After two years in Banff, Melanson stepped down from his position. The main reason: his kids – Caelan, Madeleine and Claire – were living back in Toronto with his ex-wife. Melanson made the difficult decision to leave the Banff Centre and accepted his current position with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, which he began in November 2014, bringing along his usual grand vision.

“I love the fact that the international discourse around orchestras is that they’re dying. I’m an impossiblist so I kind of love the challenge,” he says.

1999

Graduates from Laurier with MBA

1999

Dean, Royal Conservatory of Music

2004

Executive Director and CEO, National Ballet School

2012

President, Banff Centre

2014

President and CEO, Toronto Symphony Orchestra

Melanson remembers the moment he knew he would devote his life to the arts. He was in Grade 10 and during a school trip to France his class heard a choir sing in a Gothic cathedral. “This is going to sound really hokey, but it was almost like this music hit me and it just permeated my soul,” he says. “From that moment until now, my life has been about the arts and culture. That was really the moment, the turning point.”

Growing up in Winnipeg, Melanson played hockey and football and spent most of his time cheering for the Jets and Blue Bombers. He always had an interest in music, but it wasn’t until that moment in the French cathedral that he says something inside him awoke. After high school, he played it safe, enrolling in an applied math program at the University of Manitoba. But the voice inside encouraging him to follow his passion for the arts proved too strong and he switched his degree to music, focusing on voice and choral conducting.

After graduating, he performed for a few years, even doing some post-grad studying at the renowned Oberlin College and Conservatory in Oberlin, Ohio. But soon, a few realities were starting to set in.

“I became a dad, which is a moment of pause that causes you to think about what your life contribution’s actually going to be and how you’re going to pay the bills,” he says. “I also remember noticing that there were many, many people who could sing like I could sing and I started realizing I’ve really always been an ideas person.”

Around that time, a friend encouraged Melanson to consider taking his MBA. At first, he was skeptical, “I thought, ‘I can’t do an MBA, I have a music degree, you can’t go from a music degree to an MBA.’”

After realizing he was indeed qualified to enrol in an MBA program, Melanson chose Laurier based on the reputation of its program and a few recommendations from people in the business field. After moving his growing family to Kitchener-Waterloo, he quickly realized that not only did he have a knack for things like finance and valuation he genuinely enjoyed them.

Melanson was inspired by Laurier accounting professor Howard Teall, who passed away in 2004, remembering him as “an extraordinary man who had a way of synthesizing an incredible amount of detail into the life lessons we all took away.” As he continued to learn the nuts and bolts of business, Melanson started to realize how he could combine his newfound skill set with his artistic background.

“As I completed my MBA, I really realized that I could apply the combination of the business and the artistic skill sets and basically enact this vision that I have about everyone in society being creative and trying to awaken that creative potential,” he says.

The late 1990s were also a particularly interesting time to live in Waterloo Region. As Research In Motion took off and BlackBerry became a household name, the region became a hub for technical innovation and entrepreneurship.

“You could walk down the street and bump into someone who was suddenly worth millions of dollars. And these were people whose imagination was driven by building things that didn’t yet exist,” he says. “That’s what I love to do now, take these established institutions and try to re-imagine what else we can do.”

As the conversation at Roy Thomson Hall broadens in scope, Melanson is quick with a joke while discussing something he takes very seriously: the future of the arts.

Melanson’s approach to reinvigorating arts institutions has become known as “cultural entrepreneurship.” Fitting, considering his background straddling arts and business. He believes that in the current reality of declining government funding for arts programs and pervasive arguments over the relevance of the arts, some re-imagination of what arts institutions can be to different audiences is necessary.

While some of this re-imagination will inevitably involve new economic models to make arts organizations financially sustainable, money should never be the sole focal point, says Melanson.

“When we try to do something important in the world the first question is always ‘How are you going to make a living at that?’ or ‘Does it break even?’ or ‘Is it profitable?’ I’m not sure that should be the case,” he says. “We have to be thoughtful about sustainability, for sure, but that has to be weighed with what we’re trying to build.”

Economics are one threat to the future of arts and culture; another is the education system. Melanson worries that cuts in arts education will not only stunt the development of the next generation of musicians, sculptors and actors, but also have broader ramifications. “Rather than accepting that we’re in a pioneering era in terms of imagination and creativity in the economy, we’re basically still training people to do the jobs of yesterday,” he says.

“The arts inspire creativity and imagination and economically we’re in a time that requires radical, entrepreneurial behaviour.”

Despite its challenges, Melanson has a firm opinion about the future of the arts. He believes that artistic expression is ingrained in everyone — to walk is to dance, to speak is to sing, to have a pulse is to have an internal metronome.

“For art to die, humanity would have to die first.”