As an undergraduate student, Jessica Higgins (BA ’09) dealt with the death of her father and the gradual loss of her vision. Wilfrid Laurier University became her “safe haven.”

“Laurier gave me a purpose to get through that time,” says Higgins. “When I was at school, I got to feel like just another university student.”

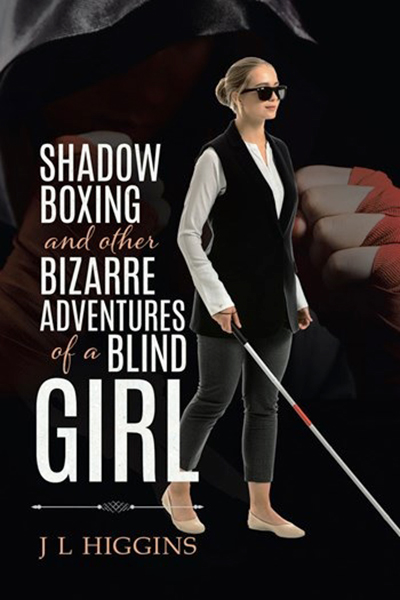

Since graduating in 2009 with a Bachelor of Arts in English and Religion and Culture, Higgins has steadily lost more of her vision due to a genetic condition called Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP), which also affects many of her family members. In 2016, at age 28, she became legally blind. It’s a journey Higgins documents in her memoir, Shadow Boxing and Other Bizarre Adventures of a Blind Girl.

“For a long time, I tried to hide it and say, ‘Be strong. This isn’t anyone’s problem but yours,’” says Higgins. “With this book, I want people to know what happened to me because I shouldn’t have kept it a secret. As a person with a disability, I have a responsibility to educate other people and help them understand.”

Higgins’s book is sprinkled with humour and optimism, a reflection of her positive attitude.

“Mine is just another joyful life full of challenges,” she says.

Why did you decide to write a book?

Laurier alumna Jessica Higgins, author of Shadow Boxing and Other Bizarre Adventures of a Blind Girl.

JH: “I actually didn’t decide to write a book. Since I was 11 years old, I have kept a journal. After my dad passed away, I would write letters to him to feel like we were still having conversations. Then, in my 20s, I started seeing a counsellor who suggested that I get back into writing since it’s a great tool for healing and getting things off your chest.

“I started writing a little bit and very quickly it turned into 50 pages. I was writing down my fears about vision loss that I had never even admitted to myself. Then when I started reading it back, parts of it made me smile and I began to wonder if I could turn it into a book.”

Shadow Boxing and Other Bizarre Adventures of a Blind Girl.

Can you explain RP and its symptoms?

JH: “RP is hard to explain because it can present very differently for each person. Essentially it is a degenerative eye condition. It gradually destroys the rods and cones in your eyes, which is why my eyesight is getting progressively worse.

“The two things that RP damages the most are your night vision and your peripheral vision. I struggle to walk into restaurants because they appear almost completely dark to me and my peripheral vision is closing in over time. It’s sort of like if you put your hands on either side of your eyes and had to look through a tunnel. That’s been my experience.”

When did you start to experience vision loss?

JH: “I was diagnosed with RP at 13, but for a long time my vision remained relatively stable. Then in my mid-20s I started to experience a really steep decline. It’s different for everyone. My mom and aunt both expressed surprise when I began cane training at the age of thirty, as they did not adopt a cane until quite a bit later in their lives. Most people with RP become legally blind between the ages of 45 and 50.”

In the book, you write about how traumatic it was to learn about your RP diagnosis. What do you remember about that experience?

JH: “I was 13, I had just found out that I would very likely be blind one day, and then I was told by my optometrist that I should seriously consider not having children because my condition is genetic. At the time, I was more devastated about being told that I would never drive a car, but 10 years later I began to realize how much anger I carried from that appointment. I think it planted a seed that I should feel ashamed and like I had done something wrong. I hope that if anyone in the medical profession reads that in the book, they reflect on it and think ‘Could I be better when I give a diagnosis to someone?’”

You write about the spectrum of vision loss and how so many people “live in the grey area between full sight and blindness.” What are some common misconceptions about individuals who are visually impaired?

JH: “There are so many misconceptions and the biggest one is that we are being rude. Now that I have my cane, I actually feel so much relief when I go out in public because I don’t need words to explain my behaviour. So often I would bump into or step on people and then have angry, confused interactions with them because they assumed that I was just being careless. People show me a lot more consideration now. Like if I’m coming up to a busy intersection, they’ll offer me an arm to cross the street.

– Jessica Higgins

“I wish there was more understanding from others, but it’s difficult because without a visual indication like a cane, it is very hard for people to understand that I’m walking around in the world successfully without an aid, and yet my vision is very, very poor. It’s an invisible disability like so many others.”

Your sense of humour comes through very clearly in the book. How does humour inform your writing and how you live your life?

JH: “Humour has always been my coping mechanism. My whole life, I have watched my mother, grandfather and aunt cope with RP by making light of it. Like them, humour helps me teach people about my condition in a more comforting way. It’s like, ‘Here’s a funny story to explain to you what night blindness is.’ The lessons are more lasting as an anecdote than they would be if I said, ‘Here are some facts about my condition.’”

Some of the chapter titles are quite funny. Can you preview Chapter 11, “Top 10 Embarrassing Vision-Related Fails?”

JH: “I had to include a list like that because I love TSN and their countdowns. The first item on the list is handshake fails. When COVID-19 happened, I started joking on day one, minute one, ‘Thank goodness we don’t have to have handshakes anymore.’ Working in financial services, there have been so many times when someone has held out their hand to shake mine and I’m grinning like an idiot, looking them in the eyes with my hands down at my thighs. And they have no idea what to do. That one got a thumbs up from the visually impaired people I know because they have all had the same experience.”

How about Chapter 14, “People’s Weird Fascination with Sneaking Up on Me?”

JH: “For my entire life, as soon as people find out that I’m visually impaired – and it doesn’t matter if it happens at work, at a bar or at a concert – they feel the need to sneak up on me. And it works every time! I probably give a better reaction than most people. I compare it to shooting fish in a barrel; you’re always going to scare me. My partner walks into the room all the time to ask me a question and I scream.”

Finally, Chapter 16, “Buffets: The Enemy of the Blind.”

JH: “That’s my favourite chapter because I love food. I love it like you love a person. So I remember being devastated when I started to lose my vision because I would get so anxious about going out and doing stuff. But I told myself, ‘I can’t lose buffets. I love them too much.’ As I write in the book, can’t we just paint arrows on the ground like they do at Ikea so we can all walk in one direction through the buffet line? Once again, it’s a funny anecdote to let people know that although this situation is comical on the outside, on the inside it can be emotional for the person experiencing it.”